Home

Restoring Nature

Restoring Nature

The global nature crisis is a real and fundamental threat to the long-term survival of our own species - alongside millions of other species that we share the planet with.

The evidence of a decline in nature over many years is clear even here in the National Park. For example, many of our Designated Sites for nature are still in unfavourable condition.

Restoring nature is about us supporting our natural environment to bounce back from damage and reduction and become more resilient and bountiful. It’s not enough anymore to conserve what we have. We need to actively stop the decline and then reverse the loss of nature. This is in our interest, as well as for other species, as nature underpins human existence through the benefits and services it provides, such as food, air, water, materials, health and economic wealth.

Restoring Nature covers three main areas:

A series of objectives and actions have also been proposed to help meet our aims in each of these areas.

You can read more about each of these areas in our Draft National Park Partnership Plan 2024-29 or click 'Next' below to learn more about how we can restore nature in the National Park.

Restoring Nature for Climate

What do we mean by Restoring Nature for Climate?

By restoring nature in the National Park we can help to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of the global climate emergency. Specifically, our peatlands and forests contain millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, and it is crucially important that we improve the ability for them to store and soak up these gases. Healthy peatlands and forests can also mitigate against the impacts of the warmer, wetter climate by acting as giant, natural sponges storing water to naturally help manage flooding.

By restoring nature in the National Park we can help to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of the global climate emergency. Specifically, our peatlands and forests contain millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, and it is crucially important that we improve the ability for them to store and soak up these gases. Healthy peatlands and forests can also mitigate against the impacts of the warmer, wetter climate by acting as giant, natural sponges storing water to naturally help manage flooding.

What is the current situation?

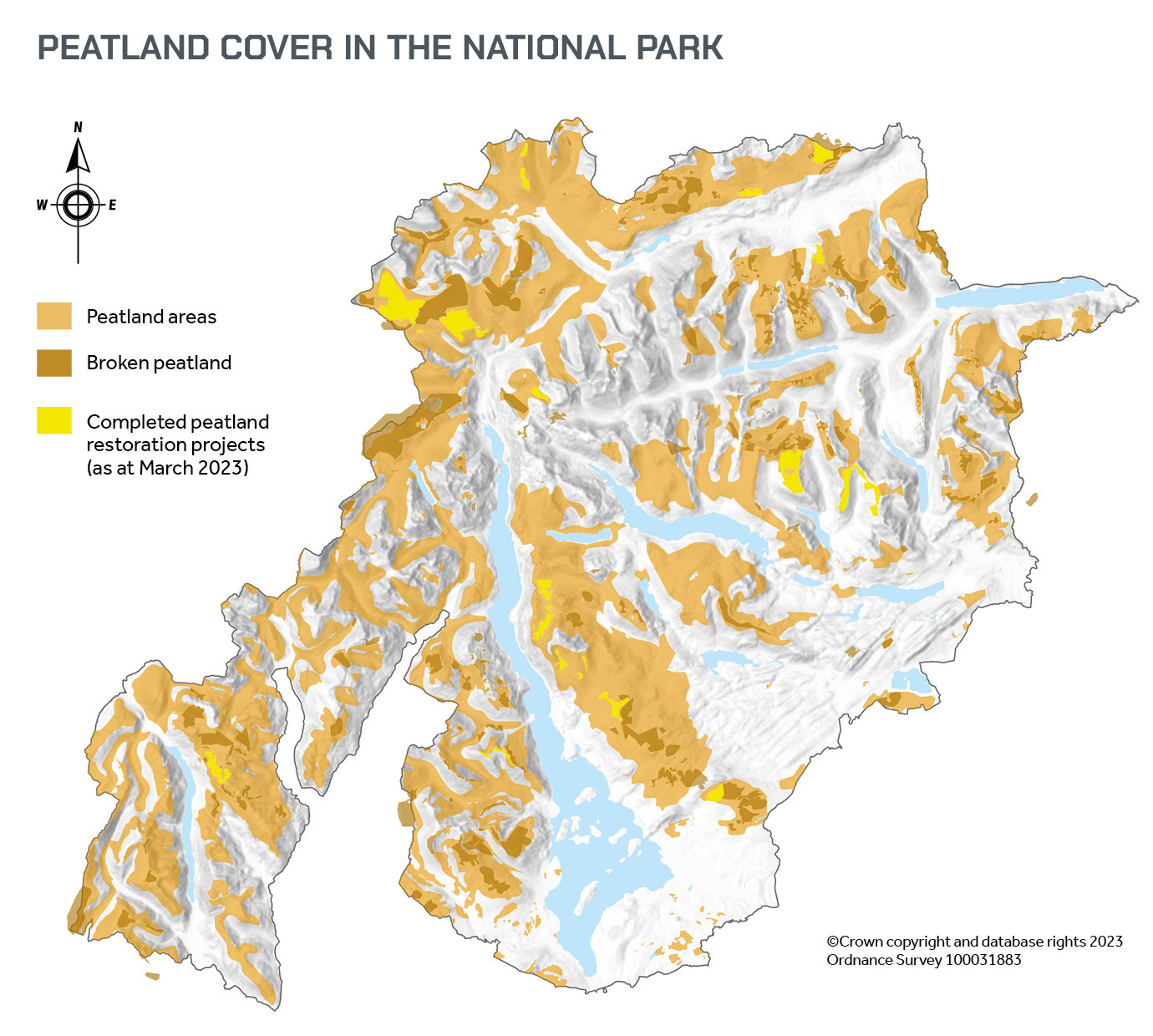

The National Park’s peatlands and forests hold an estimated 22 mtCO2e between them. But this is not secure. In fact, our peatlands are currently emitting greenhouse gas emissions, as exposed and drained peatland soils actively release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This situation can be aggravated when grazing animals like deer and sheep trample peat’s fragile surface.

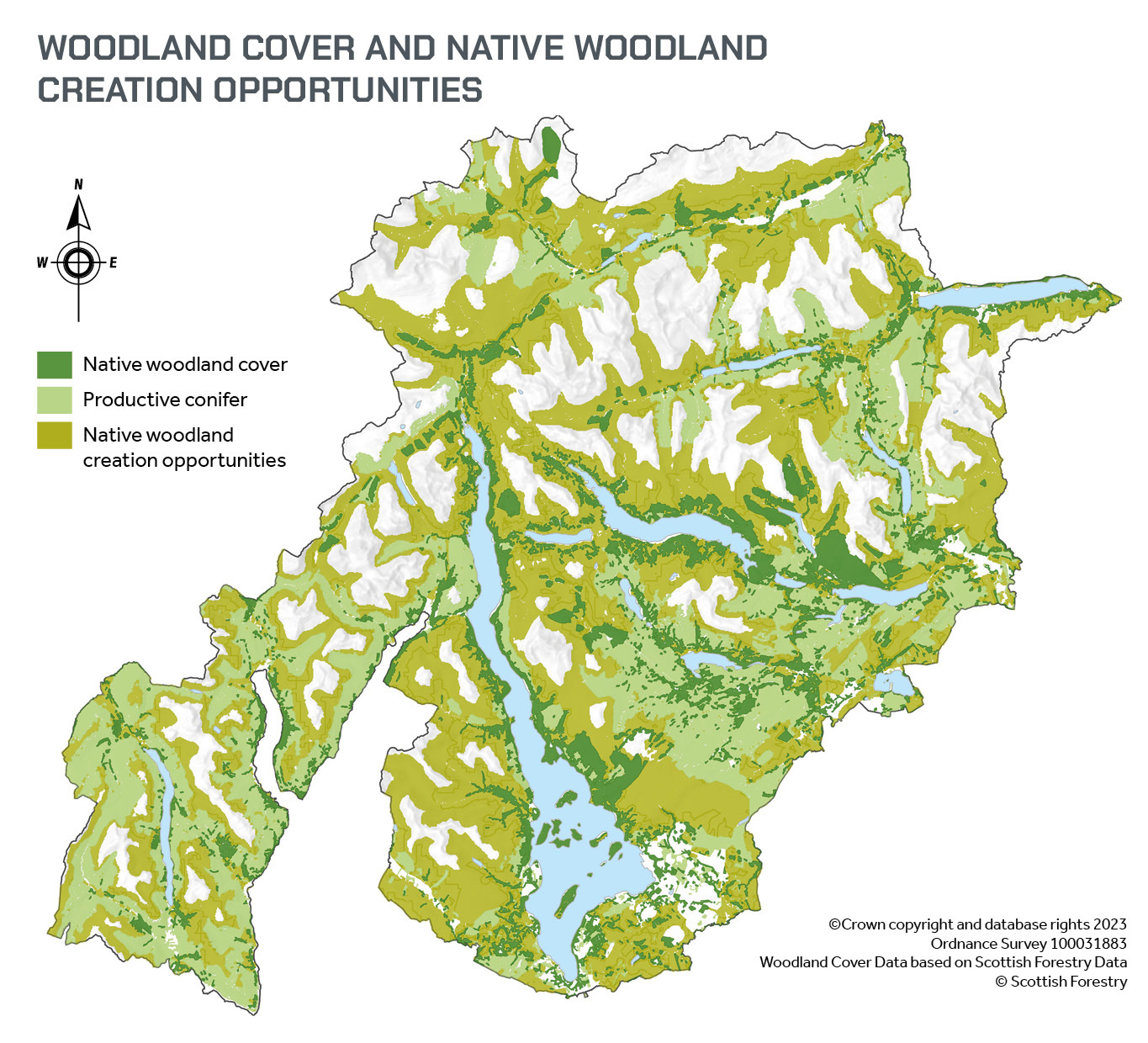

Our forests and woodlands also have great potential to store even greater volumes of greenhouse gases and act as a large carbon sink, but many of them are threatened by pressures from browsing animals, invasive Rhododendron and increasing levels of tree diseases exacerbated by a warming climate.

Some of our most special native woodlands, such as our ancient Caledonian pinewoods and Montane woodland, remain isolated and unable to regenerate due to pressures from animals grazing and preventing the growth of young trees.

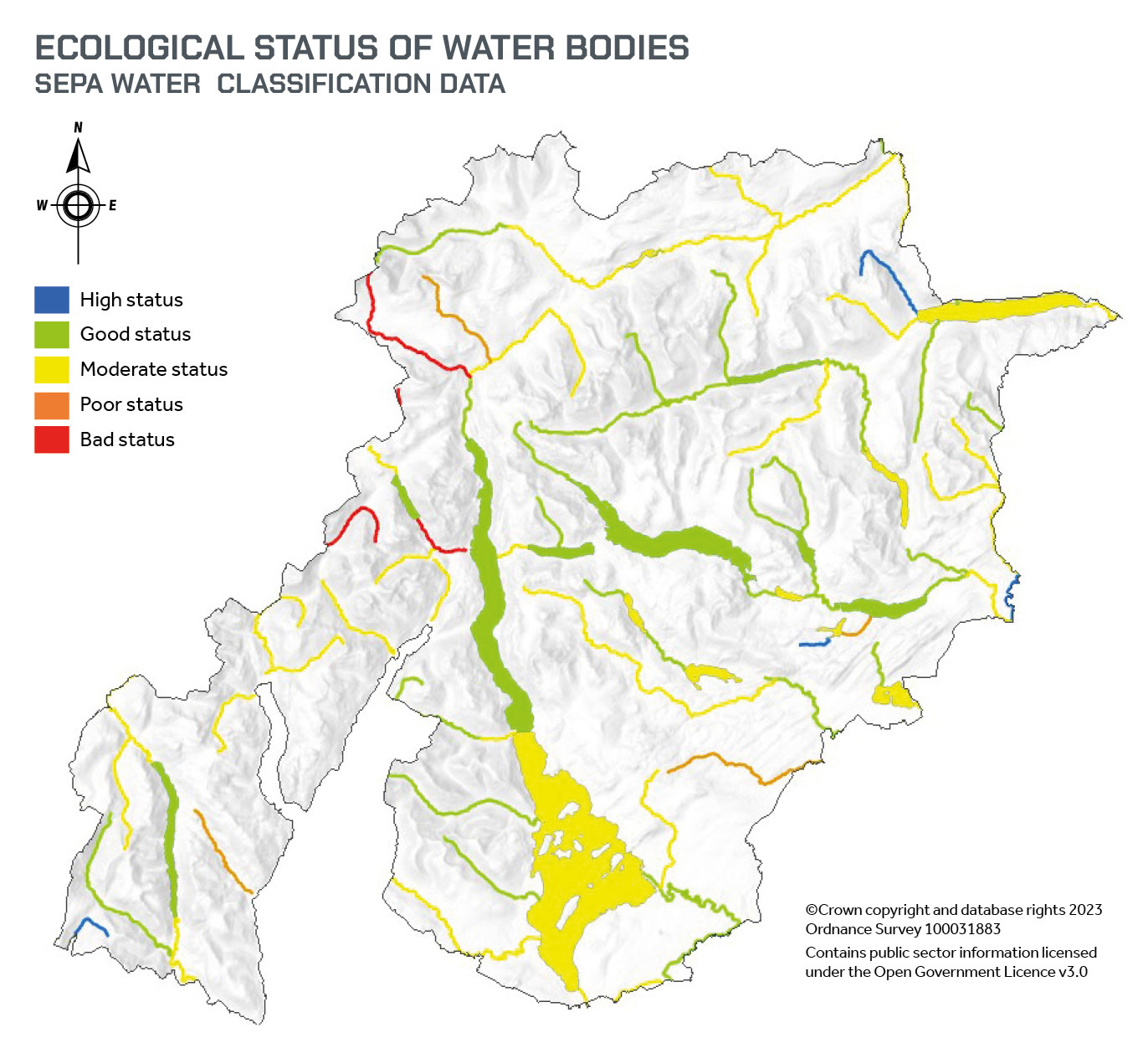

High livestock and deer pressures also negatively impact on many of our rivers, lochs and burns with natural woodland along rivers and water courses underrepresented and trampling leading to the erosion of banks with soils washing into water bodies, reducing water quality and health.

What could it be?

The National Park’s peatland areas could become sink status sites for Scotland, by capturing and locking in greenhouse gas emissions through the expansion of the peatland restoration programme and better-informed management of livestock and deer.

By expanding and improving the quality of our forests and woodlands through active management, including planting and natural regeneration, we could connect forest corridors and increase their health and resilience.

Extensive and healthy peatlands and forests could also help slow the flow of water into our rivers and lochs, providing natural flood management reducing the impact of these increasing extreme weather events on our communities.

To support a shift in land use towards more regenerative, nature friendly systems, national agriculture and forestry support and regulation schemes need to be integrated, becoming more attractive and supportive for land managers at the same time as preventing practices that erode nature.

There are already good examples in the National Park that show how land can be managed differently to restore nature and still produce food and timber.

WORK IN PROGRESS

At Glen Finglas in the Trossachs, The Woodland Trust has over 20 years protected and expanded the special native woodlands of the area while maintaining a viable farming operation.

WORK IN PROGRESS

Over the past seven years, the Peatland ACTION programme has restored more than 1,200 hectares of degraded peatland across the National Park, working with local land managers to improve the condition of uplands, which have traditionally been used for livestock and deer grazing.

WORK IN PROGRESS

In Lochgoilhead, the local community and Argyll Fisheries Trust have been working with owners to protect and enhance eroding riverbanks to improve habitats and water quality to benefit fragile fish populations.

Our aim by 2045

Our ecosystems are in good health and helping us to adapt to and mitigate against the climate crisis, supporting the National Park to be an overall net carbon sink for Scotland.

Use our interactive map to tell us where and how you think we can restore nature in the National Park.

Restoring Nature for Healthy Ecosystems

What do we mean by Restoring Nature for Healthy Ecosystems?

This is how we allow natural ecosystems, and the different habitats and species that have evolved within them, to recover from the damage and reduction caused by centuries of human modification. That means allowing trees to recover and spread again, helping peatlands to heal and re-wet after decades of drainage, and rivers to once again take slower and more meandering courses.

This is how we allow natural ecosystems, and the different habitats and species that have evolved within them, to recover from the damage and reduction caused by centuries of human modification. That means allowing trees to recover and spread again, helping peatlands to heal and re-wet after decades of drainage, and rivers to once again take slower and more meandering courses.

Our focus for restoration needs to primarily be on the key ecosystems that provide the greatest levels of biodiversity found in this part of Scotland, alongside those ecosystems that help mitigate the causes of the climate emergency. These are our forests and woodlands, our peatlands, and our wetlands with their burns, rivers and lochs.

Other habitats such as species-rich meadows and moorlands also need our help to regenerate and become more diverse and healthier.

What is the current situation?

Many people and organisations across the National Park have worked hard for years to conserve nature and there have been successes in places.

Much of the action to date has been focused on protecting our most threatened habitats and species, Designated Sites such as Special Areas of Conservation or Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), or specific projects in the wider countryside.

These actions have, however, been dwarfed by land use activities that have had damaging consequences for nature, such as the drainage of peatland or grazing pressure that prevents trees naturally regenerating. Development policies and practices have only been able to reduce damage rather than improve conditions for nature. It is only within the past few years that it has become more widely accepted that protection alone is not enough to halt the decline in nature.

Habitats such as native woodlands have shrunk and become fragmented, and water quality has deteriorated as sediments and nutrients from surrounding land are washed into our water courses and lochs. In the face of the spread of Invasive Non-Native Species, overgrazing and shifts in weather patterns from climate change, native species and habitats - such as Caledonian pine forest - are struggling to regenerate and are becomingly increasingly threatened.

Despite this, we still hold nationally important populations of rare habitats such as Atlantic rainforests and the National Park is home to over 300 national priority species and over 60 Designated Sites recognised for their special habitats and species. These are the jewels in the crown of the National Park’s natural environment and their health is vital if we are to regenerate nature more widely. They provide the key pieces in creating a large-scale jigsaw of greater biodiversity across the landscape.

Despite this, we still hold nationally important populations of rare habitats such as Atlantic rainforests and the National Park is home to over 300 national priority species and over 60 Designated Sites recognised for their special habitats and species. These are the jewels in the crown of the National Park’s natural environment and their health is vital if we are to regenerate nature more widely. They provide the key pieces in creating a large-scale jigsaw of greater biodiversity across the landscape.

What could it be?

By recovering ecosystems and species, the National Park could have a thriving and resilient landscape, with returning native wildlife and improved natural habitats coexisting alongside regenerative land uses such as modern farming, forestry and renewable energy production that is more sympathetic to nature but still produces high quality local food, energy, natural products and the jobs that go with them.

Through delivery of our Future Nature programme, we will develop of a ‘Living Network’ focusing on the three key habitat networks of woodlands, peatlands and water.

Restored peatlands and improved and expanded forests could provide places for native species to live and prosper, as well as benefits for climate and the people of the National Park. Invasive Non-Native Species could be reduced to no longer threaten our native ecosystems and more naturalised water courses could become slower and cleaner flowing. The impacts of grazing animals will also be reduced, with all these things relieving the pressure on ecosystems to allow them to naturally expand and regenerate. This would see plant, animal and bird species spread and grow, increasing their resilience in the face of climate change.

Our aim by 2045

The ongoing decline in nature will be reversed by 2030 and there will be widespread restoration and recovery of nature by 2040. A landscape scale 'Nature Network' approach will be taken improving and connecting core areas and expanding the links between these core areas across the National Park.

Use our interactive map to tell us where and how you think we can restore nature in the National Park.

Shaping a New Land Economy

What do we mean by Shaping a New Land Economy?

How land is used in the National Park is fundamental to delivering multiple benefits for everyone, but we often take this for granted. Whether land is owned by public, private or charitable organisations, our land provides services such as food, water, timber, energy and a place to enjoy recreation. However, we are increasingly aware that some of the land that we would have once traditionally viewed as primarily to produce food and timber could also now have a crucial role to play in urgently addressing the challenge we all face of the twin climate and nature crises.

How land is used in the National Park is fundamental to delivering multiple benefits for everyone, but we often take this for granted. Whether land is owned by public, private or charitable organisations, our land provides services such as food, water, timber, energy and a place to enjoy recreation. However, we are increasingly aware that some of the land that we would have once traditionally viewed as primarily to produce food and timber could also now have a crucial role to play in urgently addressing the challenge we all face of the twin climate and nature crises.

We are also starting to see changes to private and public funding that reflect changing priorities for land use focused on delivering more for climate and nature. If managed correctly, this transition of our land economy also has the potential to greatly benefit our rural communities and deliver opportunities for green jobs, skills and business development, and community involvement. So, we need to rethink how we value and prioritise different land uses in the National Park, and the economies, behaviours and cultures that drive these on this finite, precious resource.

What is the current situation?

Much of our rural land is used for production such as farming and forestry with national policies, regulation and funding mechanisms directed to supporting the supply of food, timber and related products. But this picture is changing.

Whilst the production of food and timber is essential for us all, there is recognition that the consequences of some land management activities, such as unsustainably high grazing pressure from livestock and wild deer, aren’t compatible with new climate and nature goals. Some land managers are shifting how they do things and, in some areas, more communities are getting involved in decisions around land use.

In terms of funding there are uncertainties and opportunities. The global movement to address climate change has also captured the attention of financial markets and this has been reflected in increasing land values in the Park linked with carbon. As well as a growth in small-scale renewable energy production, such as hydro-electric schemes, over recent years there has been growing interest in creating carbon markets to invest in activities that help capture (sequester) carbon as a means of offsetting the emissions that remain once businesses have fully reduced the carbon footprint of their activity. This is a potential income stream for landowners and it is hoped that similar schemes will be developed for nature with biodiversity credits too. These growing carbon markets are increasing land values and driving some land purchases across Scotland.

As well as private finance, the future of public funding for agriculture could also be changing. The Scottish Government has consulted on an Agriculture Bill, expected to be implemented by 2026. Through this process there is a need to consider whether some incentives traditionally applied to agriculture should also apply to land uses delivering nature and climate outcomes.

While there are opportunities for land managers, it is also recognised that this range of uncertainties may be inhibiting land managers from committing to making changes that affect land and will be needed to address the twin climate and nature crises.

Another challenge is in skills and capacity, where it is clear there is a gap to be addressed in order to deliver the scale and pace of change needed. This includes contractor capacity to deliver peatland restoration, woodland planting, wild deer and invasive species control at scale, and other nature restoration projects. A sustainable pipeline of long-term publicly or privately funded projects will be needed to build confidence for existing contractors and new businesses.

The Scottish Government is keen to see communities getting more engaged and greater transparency in land management decisions. There has been consultation on further proposed Land Reform measures around this, such as, for example, a potential requirement for landholdings over a certain size to prepare compulsory land management plans. The National Park Partnership Plan should have a key role in guiding such plans, building on examples such as the Strathard Framework.

What could it be?

Public funding, incentives and subsidies for land managers could be better tailored towards the nature restoration and climate mitigation opportunities that exist in the National Park to realise broader public benefits, ensuring nature restoration and climate objectives are valued equally alongside productive land uses. We need to reframe what productive land means in the National Park, to include the production of other seemingly invisible services, such as carbon sequestration and diversity of nature.

A new framework and partnership with local and national stakeholders, such as a Regional Land Use Partnership could ensure agreement on more clear land use priorities which would guide how future funding is targeted.

Creating larger scale, multi-year funding programmes could build momentum and confidence for land managers to make business decisions and for contractors to invest and grow. Through better understanding of the skills needed to support new opportunities, we could also expand training to ensure the potential for new green jobs is realised.

Developing models for blending ethical private and public investment in land use change and restoration work could ensure that opportunities from the growing interest from investors is grasped in a way that also benefits our local communities and businesses.

By getting communities more engaged in the land use issues and decisions that affect them we could ensure that wider local regeneration opportunities are also identified and supported.

Our aim by 2045

The National Park is an exemplar of a new form of best practice land use and management, where climate action, nature restoration, local produce and green jobs bring benefits for all.

Use our interactive map to tell us where you think land could be used differently for nature in the National Park.

This engagement phase has finished

...